Michigan University develops world's smallest computer, smaller than rice grain

What's the story

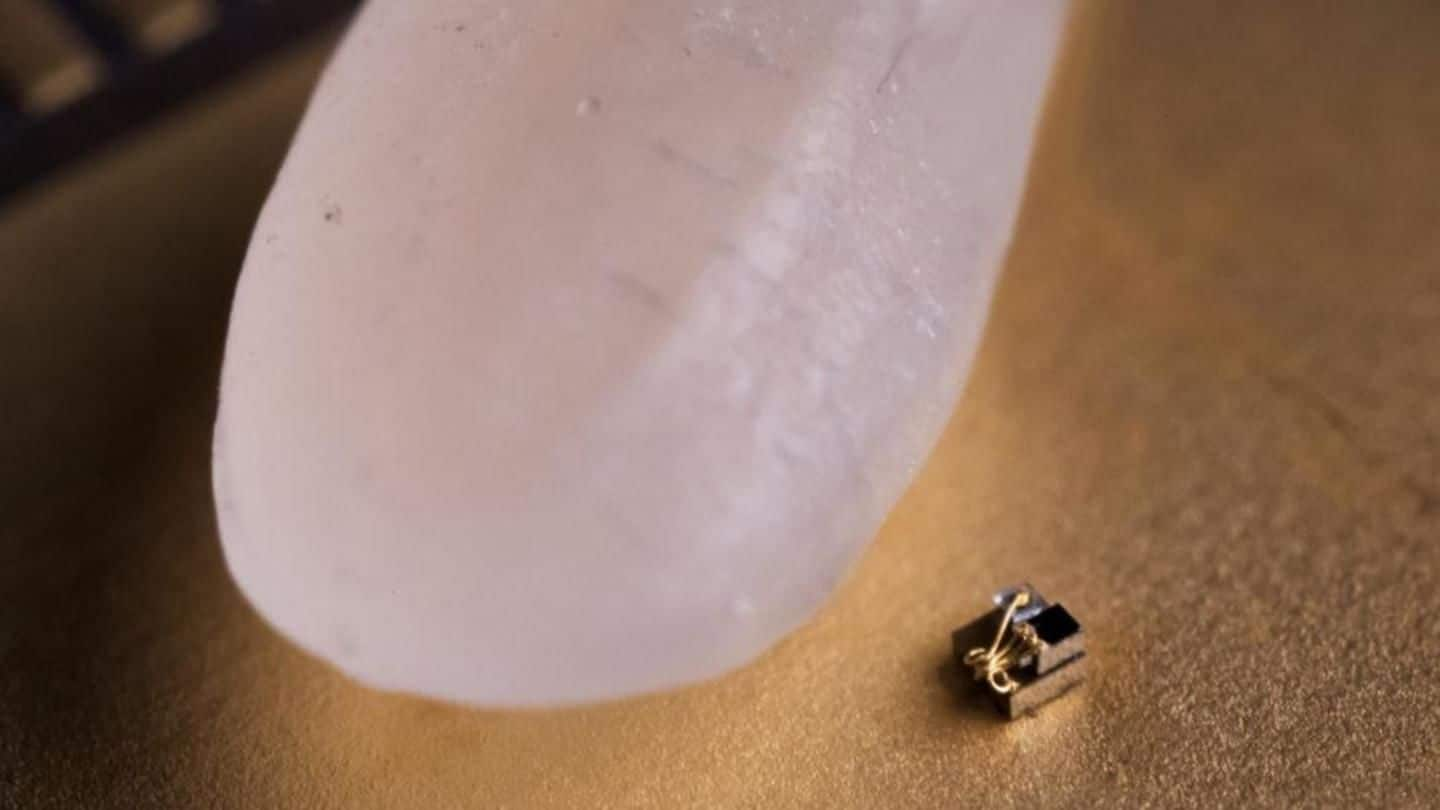

Engineers at the University of Michigan have developed the smallest computer in the world. It's 0.3 mm x 0.3 mm in size and can stand on the tip of a rice grain. The computer consists of a processor, system memory, a base station, and wireless transmitters and receivers. It uses photovoltaics, a method of converting light into electricity, for sending and receiving data.

The race

Competition in the world of tiny computing

Earlier in March, IBM developed the world's smallest computer which was 1 mm x 1 mm in size (smaller than a grain of salt) by beating the Michigan Micro Mote, which was a 2 mm computer built by engineers at the University of Michigan in 2015. Now it looks like the university has reclaimed the record.

Quote

The computer is one-tenth the size of IBM's version

"We are about 10x smaller so we can fit in smaller spaces. Also, the IBM computer can't sense its environment—it can send a code identifying itself but it does not sense its physical environment," David Blaauw, a professor co-leading the project, said.

New approach

The creation is about more than just size: Michigan University

To build a computer that small, engineers had to approach circuit design differently, something that "would be equally low-power but could also tolerate light." The system packaging of the computer is transparent which exposes its tiny circuits to light from the base station and the computer's own transmission LED. This provides it with power and programming capabilities.

Limited functionality

IBM, Michigan computers don't store data when they lose power

However, engineers are now questioning if it would be right to call the device a "computer" and if its minimum functionality qualifies it for that term. When you switch off a PC, it internally stores all the programs and data and you don't lose any material when you boot up the device again. But that is not the case with these tiny "computers."

Quote

The computer currently serves as a temperature sensor in tumors

"We're using the temperature sensor to investigate variations in temperature within a tumor versus normal tissue and if we can use changes in temperature to determine success or failure of therapy," said Gary Luker, a biomedical engineering professor working with U-M's engineers.

Potential

This opens doors for research in other fields

According to the researchers, the computer can be attuned to aid in the areas of audio and video surveillance, oil reservoir monitoring, and cancer studies. Tiny computing can also be used for pressure-sensing inside the eye, biochemical process monitoring, and snail studies. The computer is flexible enough to be molded according to requirements that crucially depend on the success of tiny computing technology.