Scientists find the first-ever active volcano on Venus: Its significance

What's the story

For the first time, scientists have found direct evidence of an active volcano on Venus. They looked into radar images taken almost three decades ago—in the 1990s—by NASA's Magellan mission. The images revealed a volcanic vent on Venus changed shape and grew significantly in size in less than a year. Here's why the findings of active volcanism on Venus carry significance.

Context

Why does this story matter?

Venus, also called Earth's twin, shares a couple of similarities to our home planet in terms of its rocky nature and its size. The Venusian atmosphere is thick, with toxic carbon dioxide-laden clouds, which makes it hard for any direct observations. While over 1,300 active volcanoes have been observed on Earth, no evidence of volcanism has been found on Venus, until now.

Previous missions

The Magellan mission could map 43% of Venus

Magellan's survey of Venus was not an easy task. The mission repeatedly orbited Venus and snapped images of the same locations multiple times. The spacecraft's orbit began to deteriorate earlier on in the mission, causing it to map lesser on each trip around the planet. In spite of the complications, the mission still managed to map 43% of Venus, at least twice.

Study

The images exhibited "telltale geological changes caused by an eruption"

"I didn't really expect to be successful, but after about 200 hours of manually comparing the images of different Magellan orbits, I saw two images of the same region taken eight months apart exhibiting telltale geological changes caused by an eruption," said Robert Herrick, a research professor from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The study has been published in the journal Science.

Study

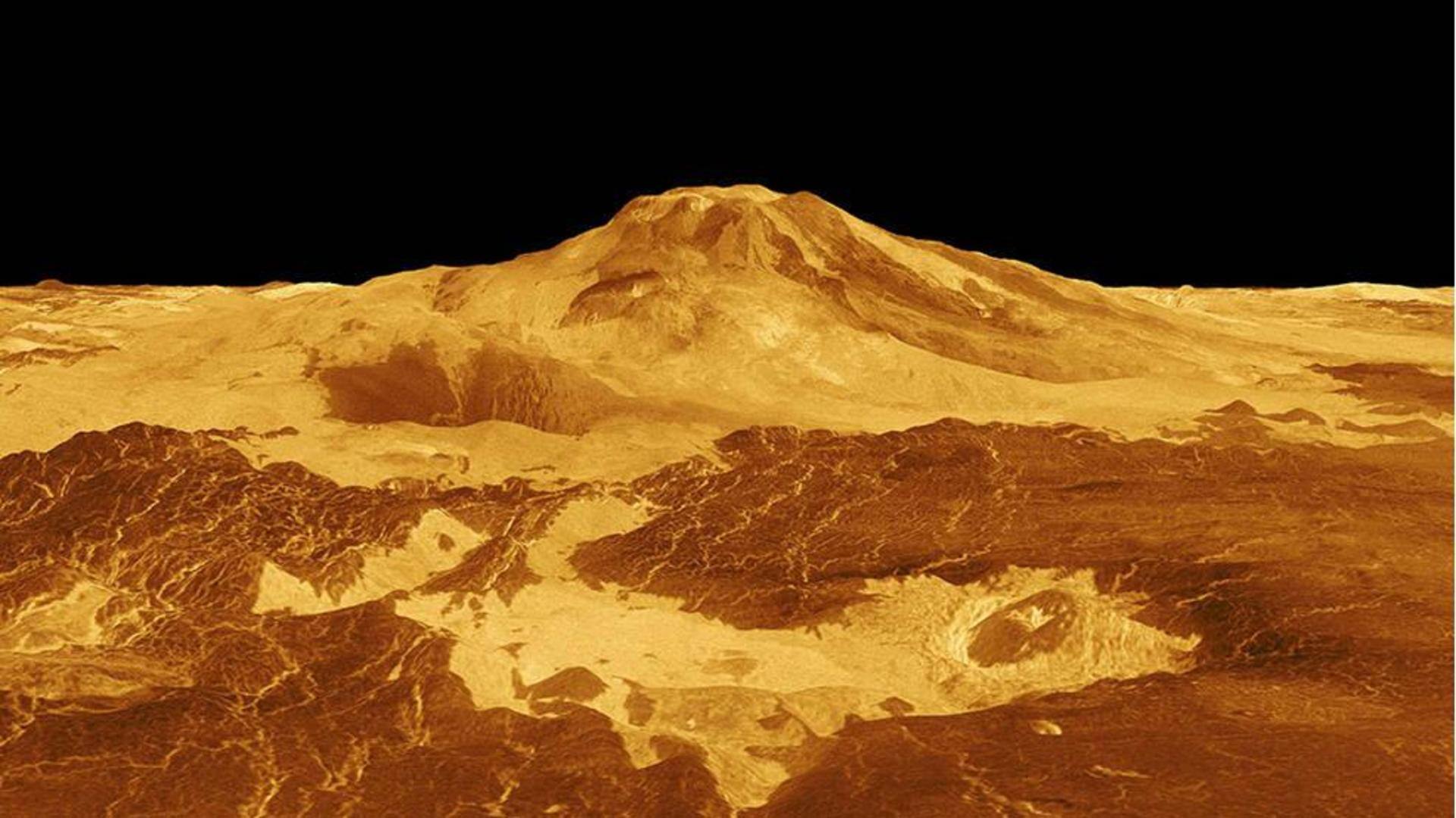

A volcanic vent associated with Maat Mons changed significantly

Geological changes were found in a region near Venus' equator, called Atla Regio, where two of the planet's largest volcanoes—Ozza Mons and Maat Mons—are situated. The area has been assumed to be volcanically active, but there was no evidence of recent activity. Upon analyzing Magellan data, it was found that a volcanic vent associated with Maat Mons changed drastically between February and October 1991.

Information

In the February image, the volcanic vent appeared almost circular

In the February image, the vent appeared almost circular, extending to an area of less than 2.2 square kilometers. The vent had steep interior sides and showed signs of drained lava down its exterior slopes, details that suggest volcanic activity.

Result

Later images reveal the same vent had deformed

In radar images snapped eight months later, the same vent had doubled in size and become misshapen. It also appeared to be filled to the rim with a lava lake. Comparing the images was difficult since the two observations were from opposite viewing angles and offered different perspectives. Further, the low resolution of the three-decade-old data only added to the complications.

Modeling

Only a volcanic eruption could have caused the change

The scientists then resorted to making computer models of the vent to test different geological-event scenarios, like landslides. From those models, they concluded that only a volcanic eruption could have caused the observed change in the vents. The researchers correlate the size of the lava flow generated by the Maat Mons activity to the 2018 Kilauea eruption on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Implications

NASA and ESA are planning different missions to Venus

Active volcanoes can shed light on how a planet's interior can shape its crust, drive its evolution, and affect its habitability. One of NASA's new missions, to Venus, dubbed VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio science, InSAR, Topography, And Spectroscopy) will do exactly that. The ESA is also planning a mission to Venus, called EnVision, which is expected to launch in the early 2030s.

VERITAS

What is NASA's VERITAS mission about?

VERITAS will use synthetic aperture radar to create 3D global maps and a near-infrared spectrometer to provide information on the composition of Venus' surface. The spacecraft will measure the planet's gravitational field to determine the structure of its interior. It will provide information about the planet's past and present geologic processes. In a recent blog, NASA said the mission will launch "within a decade."