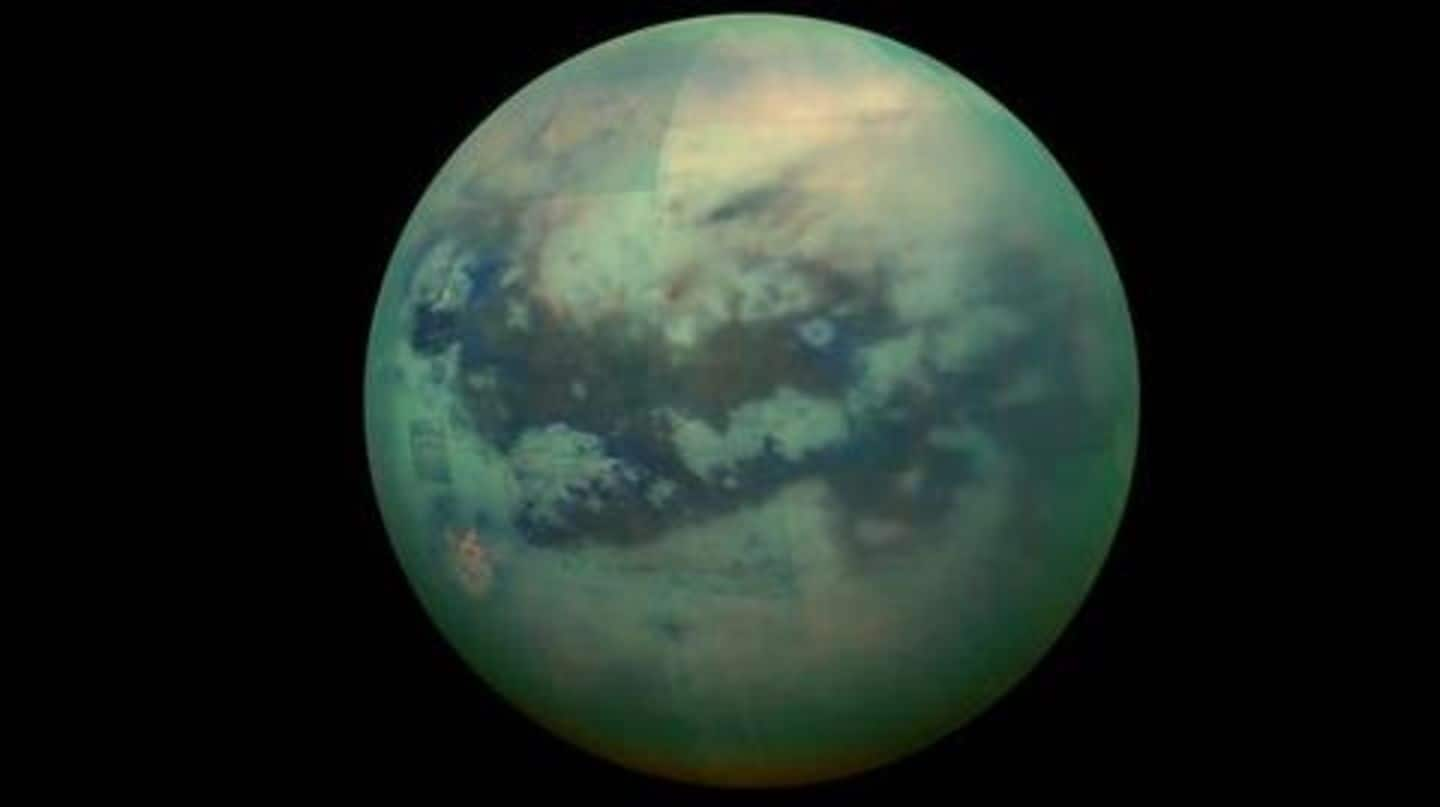

Saturn's largest moon, Titan, mapped for the first time ever

What's the story

In a major development, astronomers have mapped the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, for the first time ever. The global map of the icy, organic world highlights features similar to those seen on Earth and will largely help NASA with future missions aimed at finding signs of life or conditions that may have spurred its origin. Here's all about it.

Map

First complete picture of Titan's geological features

Scientists have long believed that Titan is an analog of the very early Earth, thanks to its dense atmosphere, Earth-like surface features, and a subsurface ocean. However, until now, what we had was broken, individual pieces of evidence proving the presence of these features. This map, however, puts together an entire picture of Titan's globe, complete with all the known geological features, their location.

Creation

How the astronomers created this map?

The global map was created by stitching together the data gathered by Cassini, the NASA probe that orbited Saturn for nearly 20 years before ending its mission life in 2017. In all, the team utilized imagery and radar measurements taken by Cassini over as many as 100 flybys of Saturn. The probe circled Saturn but got plenty of opportunities to look at Titan too.

Features

You have lakes, dunes, mountains on Titan, like Earth

The comprehensive map created by the team confirmed that the surface of Titan has several Earth-like features. It revealed that nearly two-thirds of the moon is covered by plains, while 17%, mostly along the equator, is covered by dunes. The rest includes hilly or mountainous regions, which make up 14%, and a bit of lakes, craters, and labyrinth-like terrain shaped by erosion and rain.

Information

Surface lakes are made up of liquid methane

The lakes/seas on Titan's surface make up just 1.5% of the moon and are believed to be filled with liquid methane, not water. Still, this makes Titan the only known body in space, other than Earth, where clear evidence of surface liquid has been found.

Advantage

Now, this could help NASA's Dragonfly mission

All these surface features, be it craters or lakes or plains, would ultimately help scientists delve into the evolution of Titan. Plus, the location of these features would also guide NASA in defining the sites its Dragonfly rotorcraft should explore after reaching the icy world in 2034. The mission could help the agency find signs of extinct/extant life or conditions suitable for its origin.