James Webb Space Telescope's new technique could reveal water-rich exoplanets

What's the story

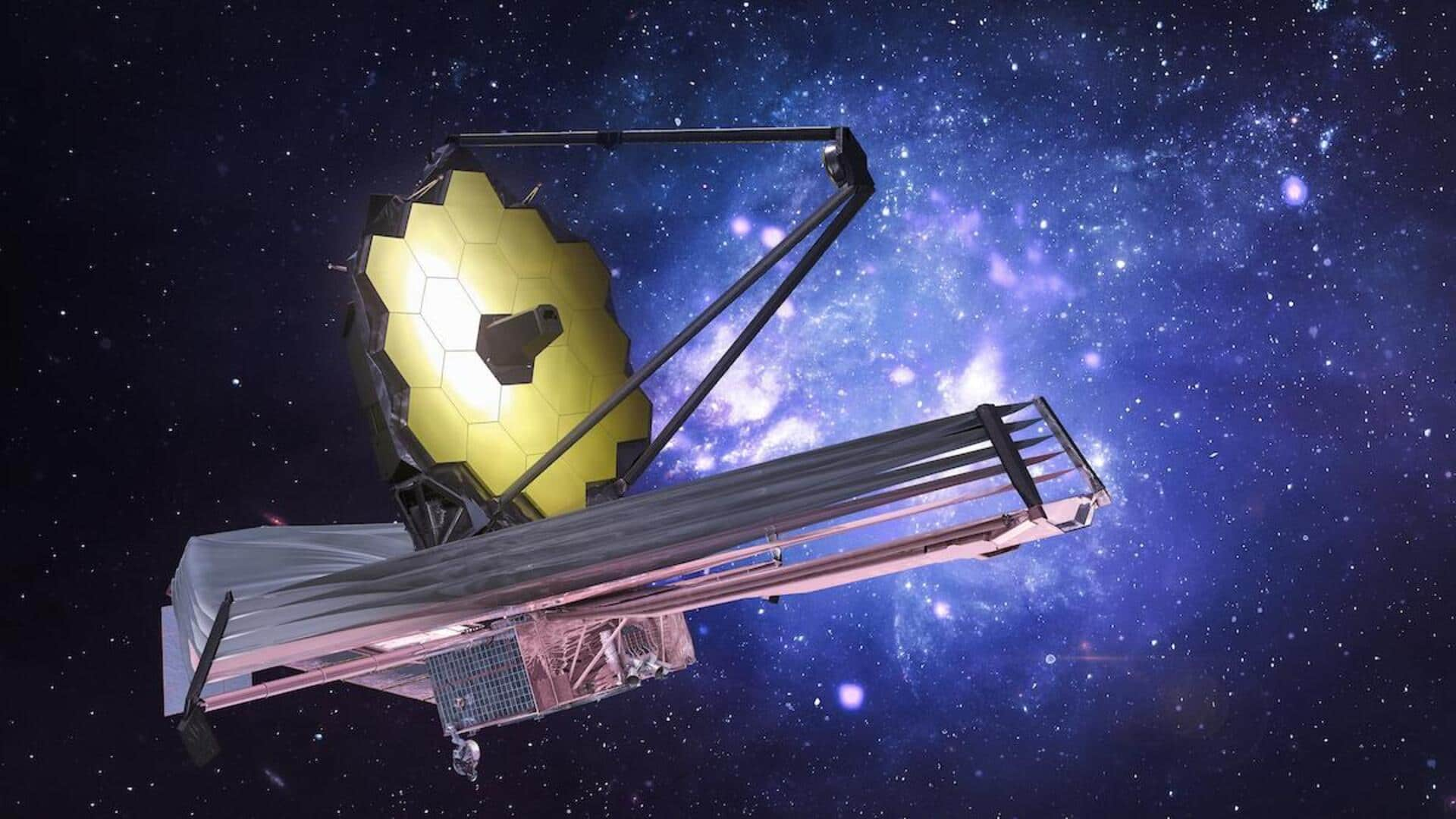

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will take a new approach in its quest to find water-rich exoplanets. It will analyze minerals present in cooled lava on these planets.

The idea is that when water meets fresh, cooling lava, it causes the formation of certain minerals in the lava.

Finding these minerals may lead scientists to the water that formed them, either on an exoplanet's surface or underground.

Volcanic significance

The role of volcanic activity in exoplanet exploration

The new approach assumes some exoplanets have cooled lava that can be studied using our instruments, indicating past volcanic activity.

This assumption is backed by evidence of lava flows on Mercury, the Moon, Mars, and Jupiter's satellite Io within our solar system.

A group of researchers has compiled a database detailing how certain minerals in cooled lava on an exoplanet might reveal themselves to JWST.

Basalt importance

Basalt: A key material in exoplanet exploration

The research team has decided to focus on basalt, a dark, fine-grained rock that forms when lava cools on a planet's surface. It is one of the most common rocks in our solar system and probably throughout the galaxy.

"We know that the majority of exoplanets will produce basalts," said Esteban Gazel, an engineer at Cornell University and co-author of a study about the database.

Water detection

Basalt analysis could reveal presence of liquid water

Analyzing a piece of basalt can tell us where it came from and how it was formed, including if liquid water was involved in its formation.

When water flows across cooling lava or through cracks in rocks, it can form minerals such as amphibole or serpentine, which are present in volcanic rocks on Earth.

These minerals should absorb and emit characteristic wavelengths of energy that JWST can detect.

Spectral analysis

JWST to measure light spectrum from distant planets

By measuring the spectrum of light radiating from a distant planet with JWST, astronomers can deduce what the source is made of.

"We're testing basaltic materials here on Earth to eventually elucidate the composition of exoplanets through the James Webb Space Telescope data," Gazel said.

The team measured light spectra from 15 basalt samples, each taken from different environments on Earth and containing a unique mix of minerals.

Data simulation

Basalt data simulation for exoplanet LHS 3844b

The researchers employed a computer program to simulate how this basalt data would look if it were coming from the surface of a rocky planet called LHS 3844b, situated some 48 light-years away.

The simulation was performed using JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

"By examining small spectral differences between the basalt samples, scientists can in theory determine whether an exoplanet once had running surface water or water in its interior," the statement said.