How scientists plan to find life on Saturn's moon Enceladus

What's the story

Enceladus, one of the 83 moons of Saturn, is called "one of the solar system's most scientifically interesting destinations."

The icy moon is known to contain salty oceans which might harbor marine life.

Researchers from the University of Arizona have revealed how the moon could be probed for signs of life by an orbiting space probe, without actually having to land on its surface.

Context

Why does this story matter?

The search for life on another world other than Earth has been endless but scientists have uncovered promising leads in recent years, and one among them is Enceladus.

It is a small, icy body measuring only about 500 kilometers wide. It is one of the brightest in the solar system and reflects almost all of the light that strikes it.

Investigations

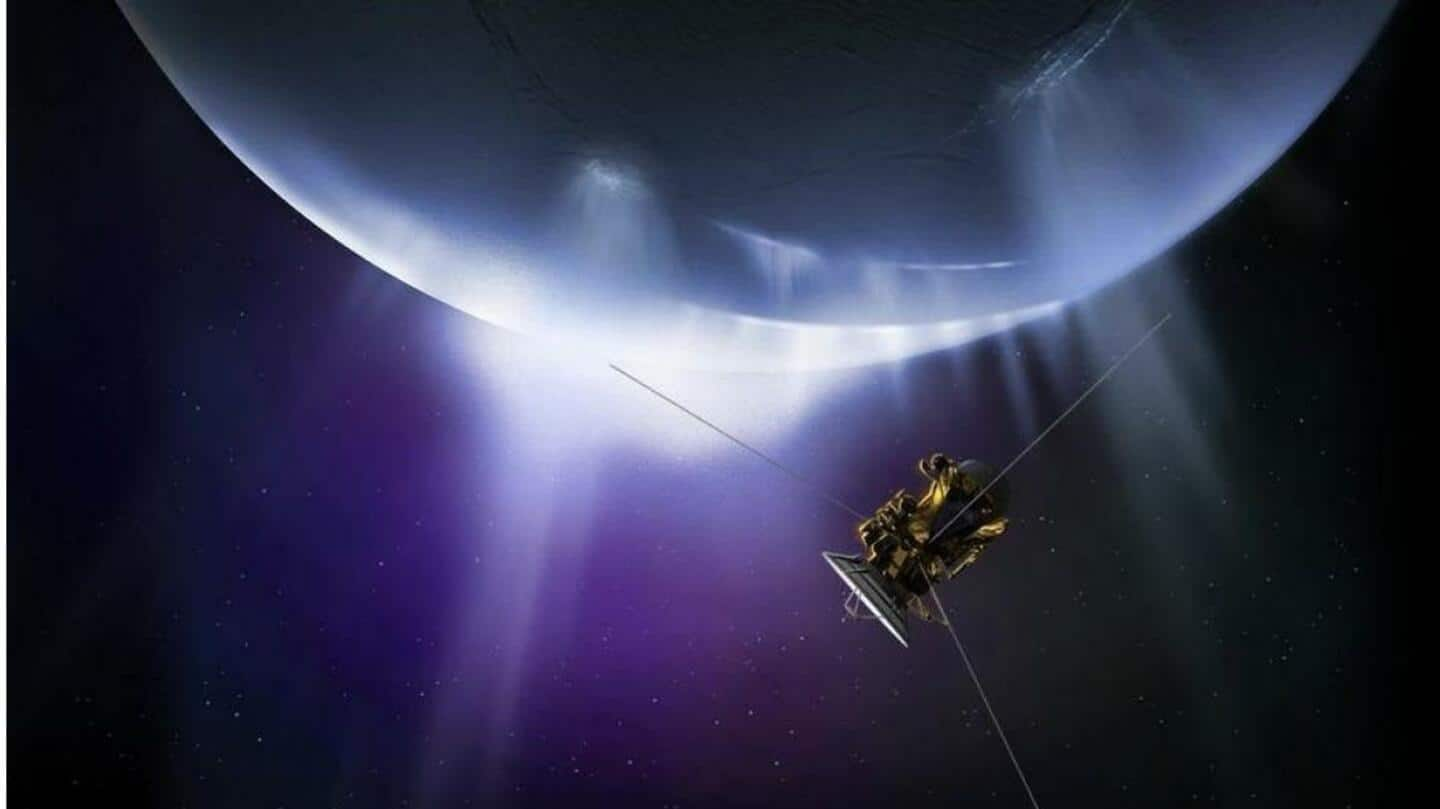

Observations from the Cassini spacecraft revealed about Enceladus' oceans

For almost 200 years, little was known about Enceladus. Investigations began with NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft in the 1980s.

It was the space agency's Cassini spacecraft that voyaged around Saturn between 2015 to 2017 and revealed that beneath the moon's thick crust of ice is a vast and warm saltwater ocean that releases methane, a gas that typically originates from microbial life on Earth.

Study

Enceladus spews plumes of water into space

Along with methane, the Cassini spacecraft also detected other life-supporting molecules on Enceladus.

The moon takes 33 hours to complete one orbit around Saturn. Along the moon's south pole, at least 100 massive water plumes erupt, like volcanoes, through the cracks of its icy surface.

The immense gravitational forces of Saturn cause the moon's interior to heat up, resulting in giant plumes.

Study

An orbiting spacecraft will be able to probe the moon

Hypothetically speaking, researchers suggest that the total mass of living microbes in Enceladus' ocean would be small.

An orbiting spacecraft, with upgraded instruments, would be able to reveal if there are Earth-like microbes on Enceladus' ocean underneath its icy shell.

"Clearly, sending a robot crawling through ice cracks and deep-diving down to the seafloor would not be easy," said Régis Ferrière, associate professor.

Official words

The new approach can determine if Enceladus' ocean supports life

"By simulating the data that a more prepared and advanced orbiting spacecraft would gather from just the plumes alone, our team has now shown that this approach would be enough to confidently determine whether or not there is life within Enceladus' ocean without actually having to probe the depths of the moon," said Ferrière.

"This is a thrilling perspective," he added.

Information

The ejected particles are believed to have formed Saturn's rings

Scientists believe that water vapor and ice particles spewed by these geyser-like plumes contribute to one of Saturn's iconic rings. This ejected mixture, which brings up gases and other particles from deep inside Enceladus' ocean, was sampled by the Cassini spacecraft.

Cassini's findings

Methanogens can survive even in the absence of sunlight

"On our planet, hydrothermal vents teem with life, big and small, in spite of darkness and insane pressure," said Ferrière. "The simplest living creatures there are microbes called methanogens that power themselves even in the absence of sunlight."

Methanogens convert dihydrogen and carbon dioxide to gain energy and release methane as a byproduct in the process.

Assumptions

The study was based on certain assumptions

Based on the hypothesis that Enceladus contains methanogens in its oceanic hydrothermal vents similar to that found on Earth, Ferrière and his research group modeled calculations.

The researchers then estimated what the total mass of methanogens on Enceladus could be, and also determined the likelihood that such cells and other organic molecules could be ejected through the plumes.

Conclusion

Amino acids are an indirect form of evidence of life

"Enceladus' biosphere may be very sparse," said Antonin Affholder, the first author of the paper.

"And yet our models indicate that it would be productive enough to feed the plumes with just enough organic molecules or cells to be picked up by instruments onboard a future spacecraft."

According to scientists, amino acids, such as glycine, could also serve as indirect signs.