How sonification is helping scientists document the wonderful universe

What's the story

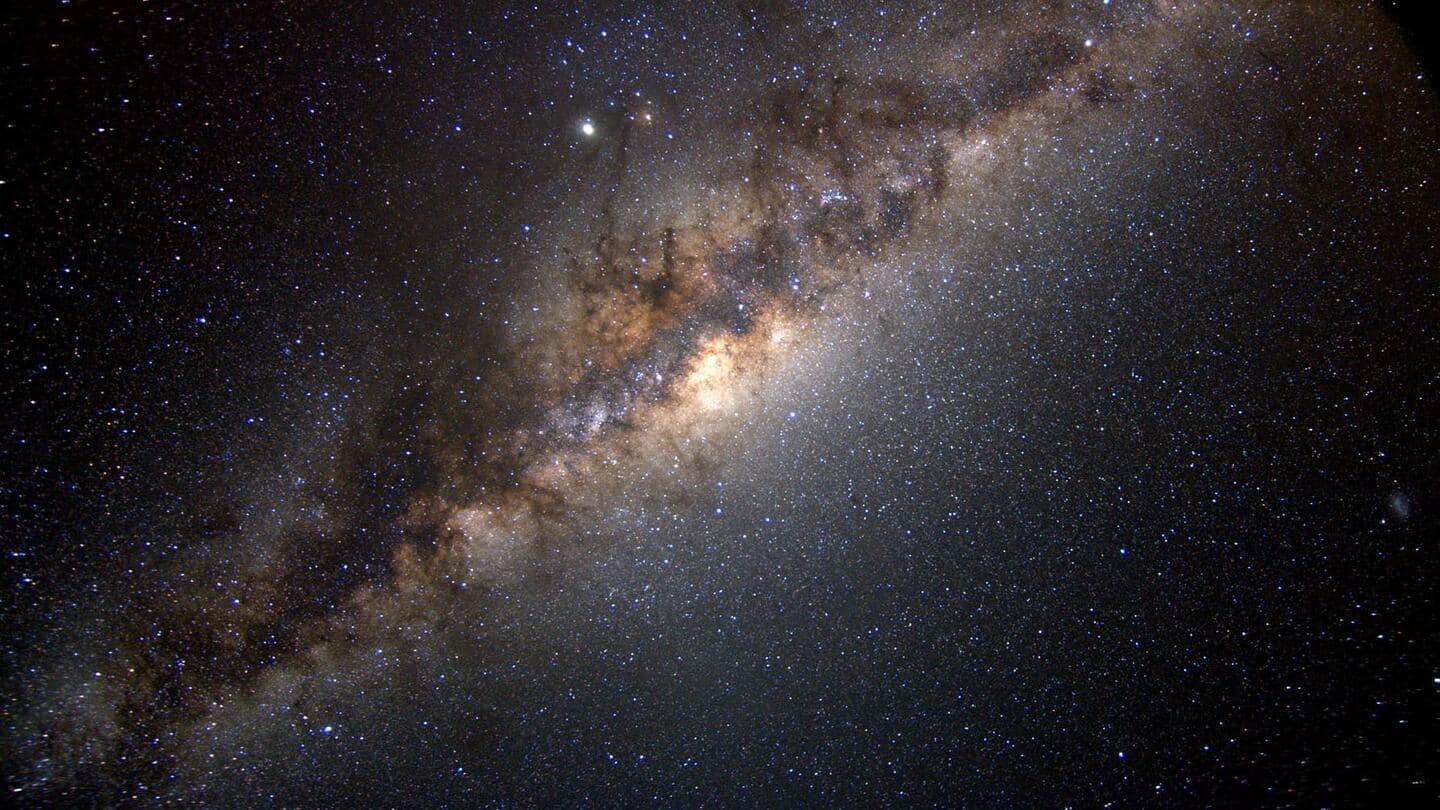

Space agencies have succeeded at photographing some extraordinary details of the universe.

But have you realized that the blind and visually impaired are at a disadvantage here? Fortunately, scientists have figured out alternative ways to convey astronomical information.

One such technique is called sonification, which converts research data into digital audio files, which can be heard, read, or even seen.

Context

Why does this story matter?

So far, we have seen images from ground-based and space observatories that have used light to capture images of the universe.

Now, the 'data sonification' technology could revolutionize the way that astronomical information is perceived and can help reach a wider audience.

This technique has also been used to study ecological shifts caused by climate change in an Alaskan forest.

Limitation

Standard visualization techniques do not provide the whole picture

The age-old method of using images, graphs, and animations to represent astronomical concepts has some limitations.

For instance, these standard visualization techniques are developed based on certain assumptions made about the information contained in the obtained astronomical data.

Scientists are often required to filter the relevant data and eliminate unimportant details. However, by doing this they might lose out critical information.

Benefit

Using sound for astronomical investigations is already in trend

Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the number of projects focused on sound-based representation.

In a recent study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers explain how astronomical datasets often contain several dimensions and using sound paves the way for making discoveries.

This technology can provide multisensory resources for students and for the general public.

Recent examples

JWST's iconic 'Cosmic Cliffs' image also has an audio version

In August, NASA tweeted about two extremely fascinating sounds in the cosmos.

The first, which has over 17 million views, was the sound of the black hole at the center of the Perseus galaxy.

The next one was James Webb Space Telescope's famous 'cosmic cliffs' image.

The team worked with blind and visually impaired individuals to convert the images into audio versions. Moreover, they are technically accurate.

Twitter Post

Listen to the sound of the black hole here

The misconception that there is no sound in space originates because most space is a ~vacuum, providing no way for sound waves to travel. A galaxy cluster has so much gas that we've picked up actual sound. Here it's amplified, and mixed with other data, to hear a black hole! pic.twitter.com/RobcZs7F9e

— NASA Exoplanets (@NASAExoplanets) August 21, 2022

Working

How were scientists able to achieve this feat?

"Sonification of an image of gas and dust in a distant nebula, uses loud high-frequency sounds to represent bright light near the top of the image, but lower-frequency sounds to represent light near the image's center," explains Nature.

Black hole sonification translates data on sound waves traveling through space—created by black hole's impact on the hot gas—into human hearing range.

Other applications

Data sonification can also provide insights into protein folding

Data sonification has also been employed for other biological applications.

Recently, biophysicists have adopted this technique to enhance students' understanding of the concept of protein folding.

Earlier in 2017, researchers tested if it can be employed for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder, from brain scans.

They discovered that sonification provided higher accuracy than the standard visualization-based diagnosis procedure.

Conclusion

The technology is at its initial phase of development

Needless to mention, this technology is still in its infancy. Although it furnishes technically accurate results, there are no universally accepted standards for sonifying scientific data as yet.

Another major problem is funding. Scientists often collaborate with musicians or sound engineers to transform their scientific data to sound and this becomes challenging when there isn't a stable source of funding.