Astronomers detect 'Pyrene,' a key molecule for life, in space

What's the story

In a groundbreaking discovery, astronomers have unearthed one of the largest carbon-based molecules ever found in deep space.

The molecule, dubbed pyrene, was found nestled within the Taurus molecular cloud some 430 light-years away from Earth.

The finding could potentially help solve a long-standing mystery in astrochemistry: the origin of carbon, an essential building block for life.

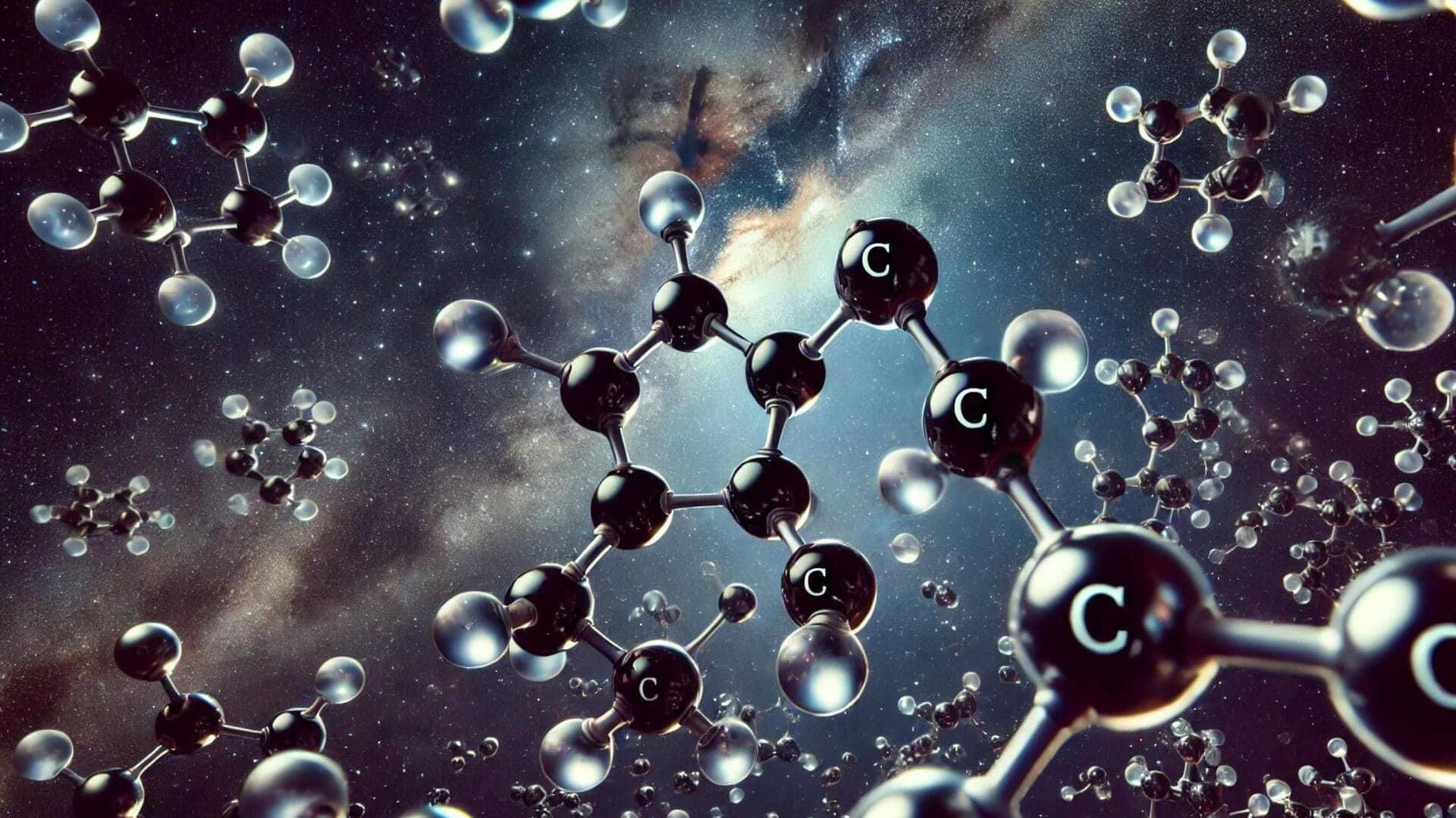

Molecule structure

Pyrene: A complex molecule in the universe

Pyrene is a complex molecule, made up of four fused planar rings of carbon. It belongs to the family of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), some of the most abundant complex molecules in the visible universe.

PAHs were first detected in the 1960s, when they were discovered in meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites, which are leftovers from our solar system's primordial nebula.

Carbon presence

PAHs are a significant component in space

PAHs are believed to make up about 20% of the carbon in space, serving an important function at different stages of a star's life.

Their stability and resistance to UV radiation makes them likely survivors even in the extreme conditions of deep space.

The hunt for pyrene and other PAHs in the Taurus cloud was launched after high concentrations of pyrene were found in samples from near-Earth asteroid Ryugu.

Discovery method

Radio astronomy: A tool for space exploration

The discovery of pyrene was made using radio astronomy, an important branch of astronomy that studies celestial objects in the radio spectrum.

Unlike other tools used to identify molecules in space, radio telescopes can observe individual molecules by detecting their unique "fingerprints" of electromagnetic radiation.

This technique proved useful in identifying pyrene and its role as a potential source of carbon in space.

Abundance surprise

Pyrene's abundance and formation in cold environments

Astronomers estimate pyrene constitutes roughly 0.1% of the carbon present in Taurus cloud—a number which Brett McGuire, assistant professor of chemistry at MIT, described as "an absolutely massive abundance."

Interestingly, despite PAHs usually forming during high-temperature processes on Earth like fossil fuel combustion, they were discovered in a cloud with temperatures up to -263 degrees Celsius.

This unexpected finding has led to speculation about whether PAHs can form in extremely cold environments or if they come from elsewhere.