Groundbreaking study identifies lupus cause and potential cure

What's the story

A team of scientists from Northwestern Medicine and Brigham and Women's Hospital have pinpointed a molecular defect that contributes to the pathologic immune response in systemic lupus erythematosus, commonly known as lupus. The study, published in Nature, suggests that reversing this defect could potentially reverse the disease itself. Lupus affects over 1.5 million people in the US causing life-threatening damage to multiple organs including kidneys, brain, and heart. Until now, the causes of lupus remained elusive.

Treatment limitations

Current lupus treatments inadequate, says study

Current treatments for lupus often fail to control the disease and can have unintended side effects such as reducing the immune system's ability to fight infections. According to Jaehyuk Choi, an associate professor of Dermatology at Northwestern Medicine and co-corresponding author of the study, all current lupus therapies have been broad immunosuppressants up until now. He added that identifying a cause for the disease has led to a potential cure without the side effects of current therapies.

Imbalance identified

Researchers identify imbalance in lupus patients' immune responses

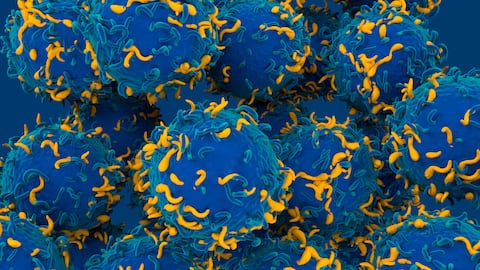

The researchers discovered an imbalance in the immune responses of lupus patients and identified specific mediators that could correct this imbalance to dampen the pathologic autoimmune response. The study reported a new pathway that drives disease in lupus involving changes in multiple molecules in patients' blood. These changes lead to insufficient activation of a pathway controlled by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), which regulates cells' response to environmental pollutants, bacteria or metabolites.

Potential cure

Potential cure for lupus found in reprogramming immune cells

Insufficient activation of AHR results in an excess of disease-promoting immune cells known as T peripheral helper cells that promote the production of disease-causing autoantibodies. The scientists demonstrated that returning aryl hydrocarbon receptor-activating molecules to blood samples from lupus patients could reprogram these disease-causing cells into Th22 cells. These Th22 cells may promote wound healing from the damage caused by this autoimmune disease.

New treatments

Targeting the AHR pathway and interferon levels

Choi explained that their findings suggest activating the AHR pathway with small molecule activators or limiting excessive interferon in the blood can reduce the number of disease-causing cells. If these effects prove to be durable, they could potentially lead to a cure. Choi and his colleagues aim to develop new treatments for lupus patients. They are currently focused on finding safe and effective methods to deliver these molecules to people.