Vaccine-derived polio under spotlight after suspected case detected in Meghalaya

What's the story

The World Health Organization (WHO) is currently investigating a suspected case of poliomyelitis (polio), detected in a two-year-old child from Tikrikilla, Meghalaya. The Health Ministry stated that this is not a case of wild polio, but rather of vaccine-derived polio, in which an infection occurs in people with low immunity. This occurrence has caused alarm, given India was declared polio-free in 2014, with the last case reported in 2011.

Disease profile

Understanding polio and its vaccines

Polio is a highly infectious disease that targets the nervous system and primarily affects children under five years old. However, unvaccinated individuals of any age group can contract this disease. The virus is transmitted person-to-person via the fecal-oral route through contaminated water or food. Initial symptoms include fever, fatigue, vomiting, headache, pain in the legs and stiff neck. Severe cases can lead to irreversible paralysis or even death.

Vaccine overview

Polio vaccines: A double-edged sword

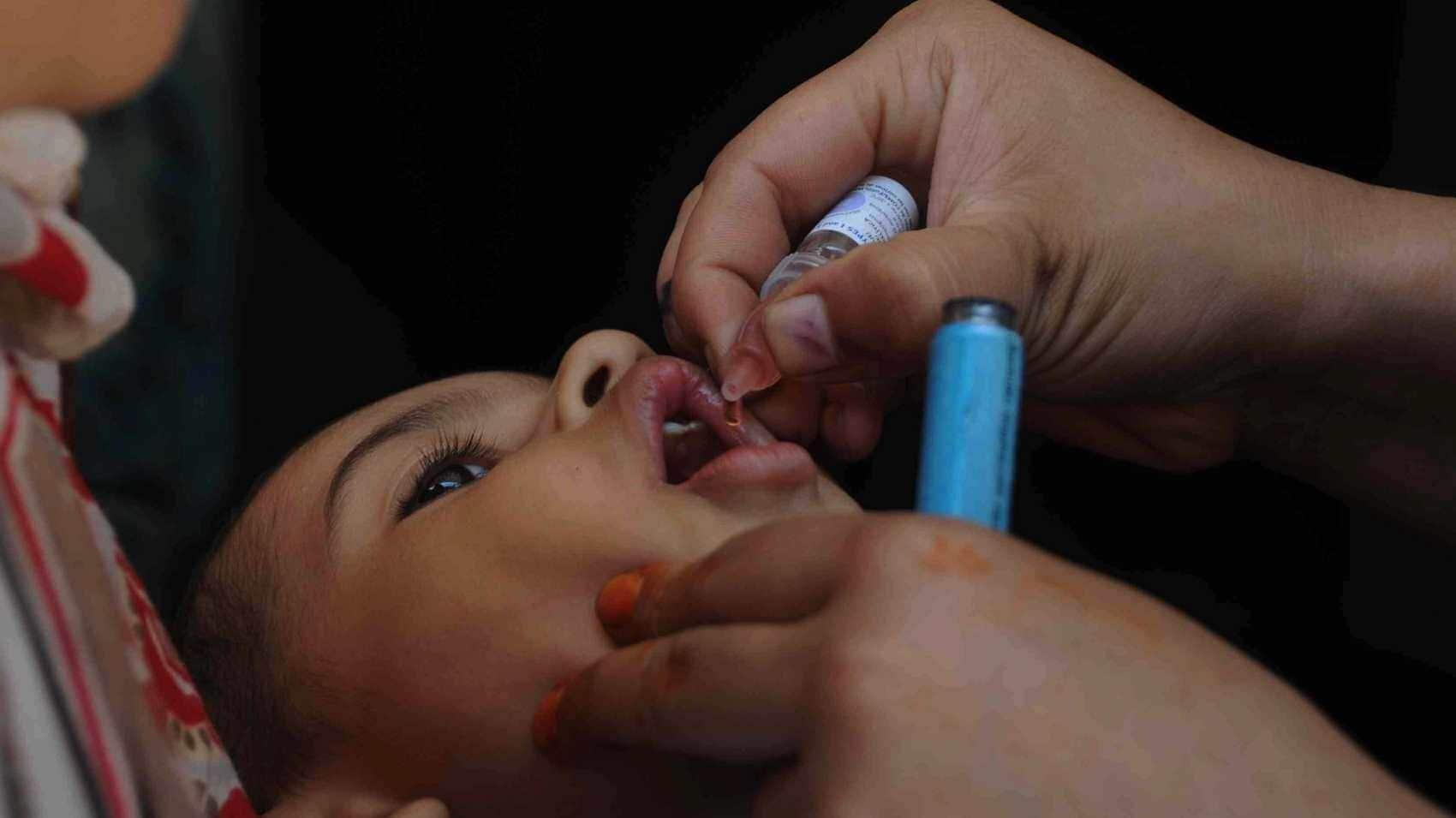

There are two types of vaccines available to combat poliovirus: the oral polio vaccine (OPV) and the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). The OPV is administered orally and contains a live, weakened form of the virus. In contrast, IPV is injected and contains inactivated strains of the virus. While these vaccines are generally safe, there have been instances where weakened viruses in OPV mutate into vaccine-derived polioviruses.

Mutation risk

Vaccine-derived poliovirus: A rare but real risk

Dr. Rakesh Mishra, Director at Tata Institute for Genetics and Society, explains that the weakened virus in OPV can replicate and mutate into new variants. This is especially true if given to a child with weak immunity, allowing the virus to remain in the body for an extended period. Over time, this virus can mutate into a form that regains its paralytic capabilities, similar to wild poliovirus.

National efforts

India's journey toward polio eradication

In the 1990s, India accounted for most of the global polio cases. In 1995, the government of India launched the Pulse Polio Immunization Program. This initiative aimed at 100% coverage and involved healthcare workers, policymakers, and community workers. Their efforts ensured every child under five was vaccinated, regardless of previous vaccination status. These measures led to a significant reduction in cases and helped India achieve polio-free status by 2014.

Vaccine debate

Ongoing debate over oral polio vaccines in India

While very effective, the OPV can induce vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) in around one in every 2.7 million doses. Dr. Mishra suggests that with cases of wild virus polio eradicated, India could consider switching to IPV. He states, "OPVs keep the virus in circulation. Considering the associated risk, although very rare, we may stop using the oral vaccine and continue using intravenous one if necessary."