Sabarimala row: Why Young India needs to look beyond religion

What's the story

The row over the Supreme Court's Sabarimala verdict has seen India sharply divided. Violence has erupted, and political parties have been quick to draw battle lines. Yet, for all the hue and cry, the Sabarimala row is a simple question of political priorities, and in the larger scheme of things, is an important battle that weighs heavily on India's future as a democratic polity.

Sabarimala row

Recap: The row over the Supreme Court's verdict

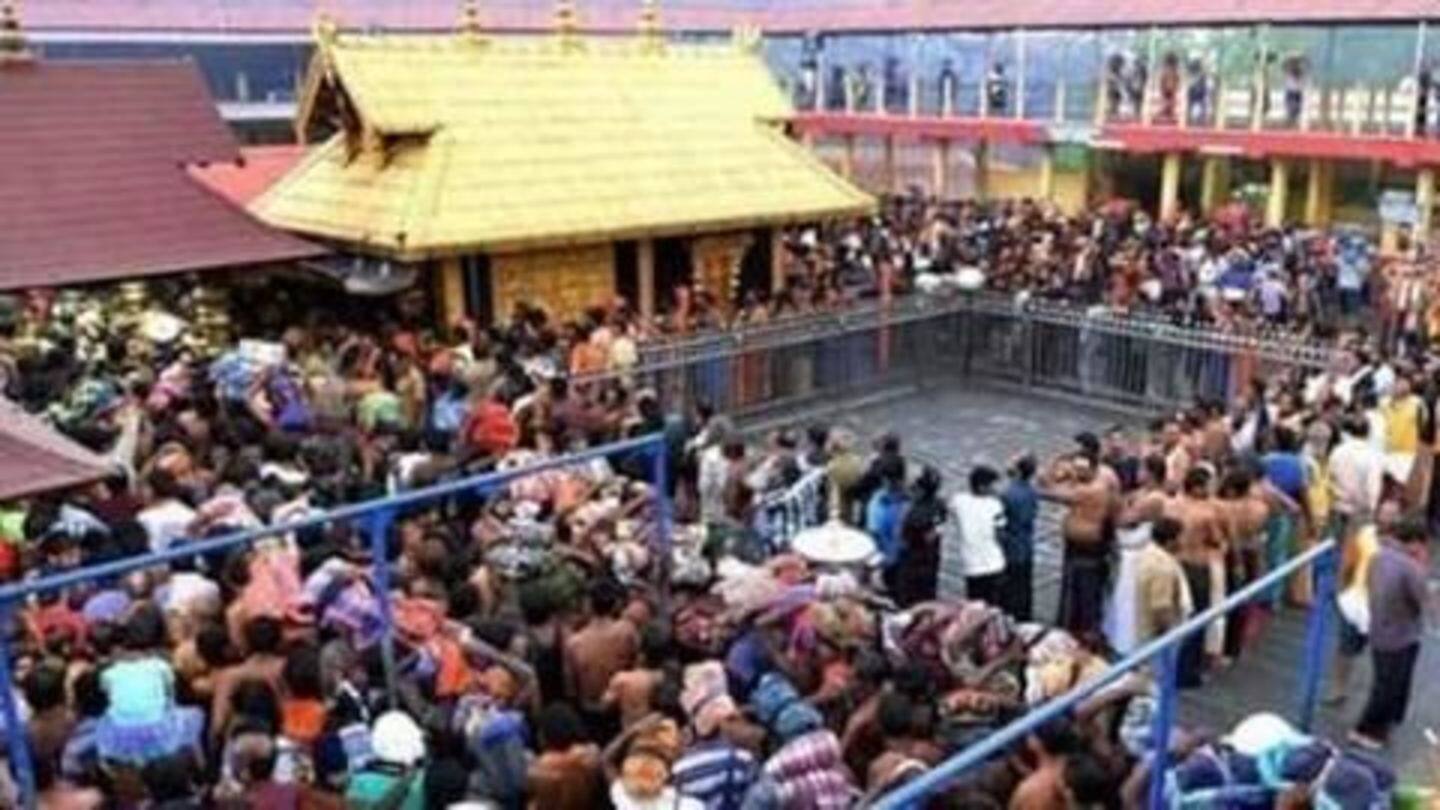

The Supreme Court, last month, quashed a ban on the entry of women of menstrual age to the Sabarimala temple, breaking an 800-year-old (regressive) tradition. Despite the Kerala government's efforts to implement the progressive ruling, throngs of enraged Ayyappa devotees blocked the entry of women and clashed with police. Political parties, looking for electoral mileage, quickly sided with the devotees, and BJP chief Amit Shah even promised to 'save' Sabarimala (from menstruating women, I suppose?).

Break-it-down

What the Sabarimala row is essentially about

A lot has been said about the Sabarimala row too, with arguments ranging from protecting the religious sentiments of Ayyappa devotees, to upholding the Constitutionally-guaranteed rights of women. Yet, when you break it down to its basics, the row is essentially about ancient religious edicts clashing with contemporary values that are increasingly being shaped by global discourses on rights and empowerment.

Indisputability

Back-to-basics: The role of religion in human history

That said, it is important to understand religion's role in human history first, before moving on. Organized religion, as a social institution, draws its legitimacy from divine power. Divine power or the concept of God, in turn, has historically been used as a terminator to an infinitely regressing question (who created/where did all this come from?). Thus, with divine sanction (which could hardly be questioned in pre-modern times), religion served as an indisputable form of social control.

Indispensability

Once upon a time, religion served practical functions

Throughout most of human history i.e. before the formal body of knowledge called 'Science' came up, religion served several practical functions too, which made it quite indispensable. Healing, medicine, ethics, formal education, interpretation of weather patterns, etc. all fell within the domain of religion and those who controlled it i.e. the priestly classes. However, this indispensability, coupled with its indisputable nature, made religion the perfect tool for establishing hegemony and maintaining status quo.

The Enlightenment

Religion lost all practical use after the emergence of Science

Thus, organized religion, in all its names and morphs, enjoyed unquestioned importance for millennia. Fast forward to the European Enlightenment era, and the emergence of Science. Rapid developments in scientific theory and consequent technological advancements, in the course of a couple of centuries, stripped religion of all of its practical uses, leaving it with only immaterial importance and a weakening foundation, wherein only the (uncritical) devotion of its supporters ensured its survival as a social institution.

Indoctrination

Religion generates devotion largely through indoctrination

So, where did this devotion come from? Well, to be fair, most of us never had a choice. Religion, whichever it might be, works through indoctrination (for lack of a better word). Children, who are otherwise correctly deemed to be incapable of making political and economic choices till they come of age, are 'indoctrinated' into their parents' religion right after birth. If an individual is deemed unfit to make autonomous choices till they reach a certain age, how can they comprehend, much less question religion and its supporting tenets at infancy?

Perpetuation

Indoctrination ensures the survival of religious tenets, rituals, and practices

It is precisely this indoctrination at an early age that allows religion to largely escape the test of criticality. Children 'indoctrinated' into one religious fold or the other, grow up believing in the tenets, rituals, and practices of the religion because they lack the knowledge and criticality to question them. Questions, when raised, are answered with ambiguous theological rhetoric, and the religion allotted at birth, in most cases, becomes a large part of the individual's identity.

Compatibility

Religion has become incapable of molding itself to contemporary values

By becoming an integral part of a person's identity and by creating a larger collective identity, religion ensures that its age-old edicts are upheld generation after generation. Although this worked for millennia in ensuring religion's perpetuation, in today's age, it has left religion incapable of molding itself to the rapidly changing values and ethics of contemporary society, which in turn are shaped and accelerated by scientific advancement and the processes of globalization.

In context

The Sabarimala ban in today's age cannot be justified

Now, place this in the context of Sabarimala. The 800-year-old ban on the entry of women of menstrual age stemmed from an unscientific principle of purity and pollution. However, with the emergence of Science, and with the even more recent emergence of women's rights discourses, this principle and the ban have become scientifically, rationally, and ethically unjustifiable.

Choice

The Sabarimala row has two possible outcomes

This has essentially left devotees and temple authorities with two choices - allow women's entry (which would contradict age-old religious tradition and undermine religious authority), or scream in protest alleging that religious 'sentiments' have been offended. Surely, from the point of view of religion as a social institution, the latter seems to be the more desirable plan of action as it ensures no undermining of its authority.

Outcome

The failure of the state should not be taken lightly

Indeed, the same has been demonstrated in the row over the Supreme Court verdict, and the failure of the state to implement the verdict should not be taken lightly. If anything, the Sabarimala row demonstrates the power of religion as a social institution in India and its potential to block social progress and undermine the rule of law to protect outdated, irrational beliefs. Further, it's highly likely that many similar disputes will follow in future.

To conclude

Time for the citizenry to choose

Therefore, it is not just up to political authority, but also up to citizens to decide which they prioritize more - protecting age-old, often regressive edicts that they have been conditioned to believe in, or ushering in progressive social and legislative change that might run contrary to dated religious beliefs. Sadly for fence-sitters, there's no middle ground here - we have to choose, either today, or tomorrow.