Manto: A storyteller, a cynic and a troubled soul

What's the story

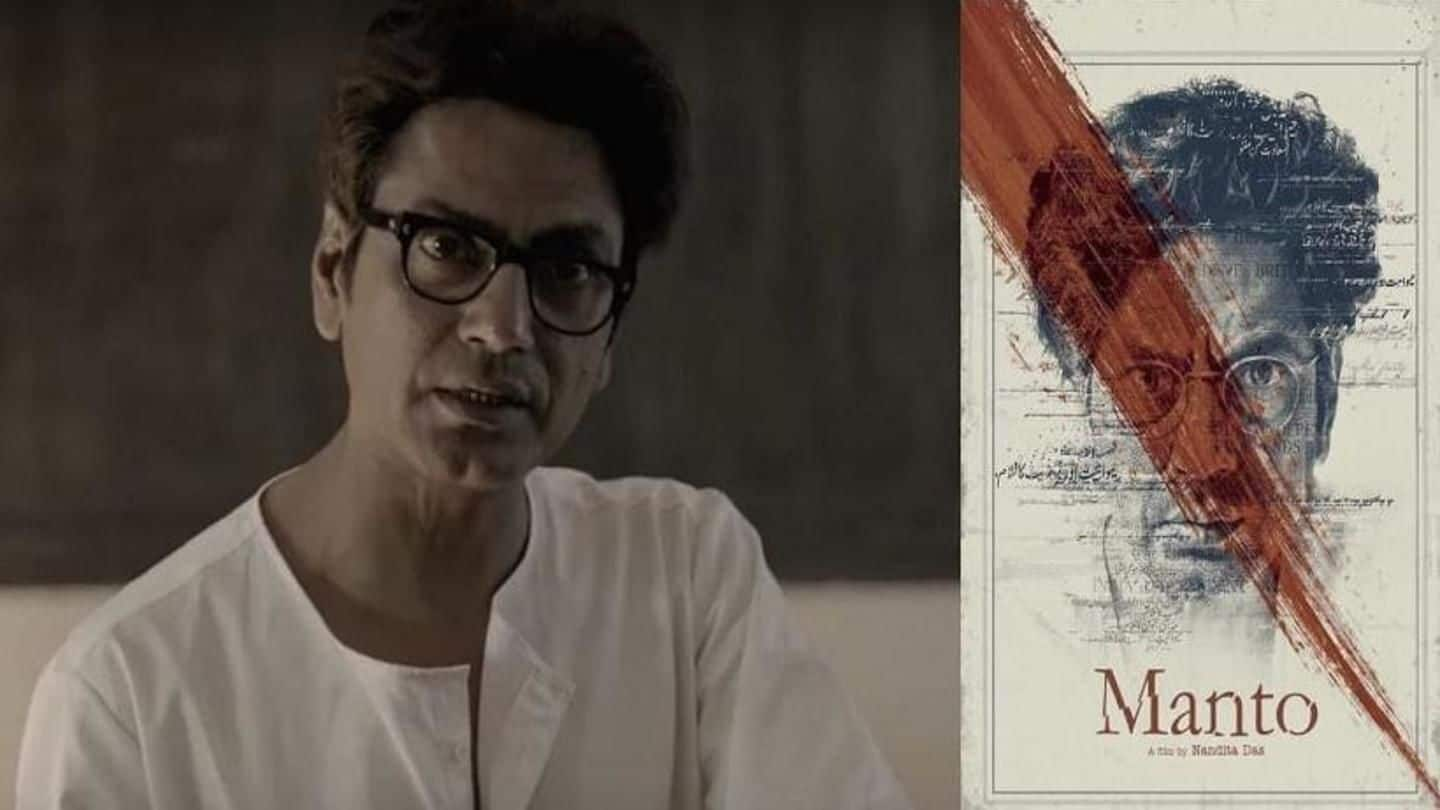

As Nandita Das' biopic of 'Manto' starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui is all set to release tomorrow, we take a look at the hype around the inscrutable writer. Unlike us, he didn't run away from controversial subjects. He wrote about them during a time when India was way more "moralistic", and sadly, just as communal. We decipher what he stands for, his principles, his beautiful writings and why reading Manto is imperative now, more than ever before.

Details

My first encounter with Manto

"If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty. With my stories I only expose the truth." Take a minute to absorb these lines, and then take a lifetime to fully absorb them. I read Manto at a tender(?) age of 13. The first story, I read, was 'Khol Do.' It's a story of Sirajuddin, whose wife was killed in the riots, and daughter Sakina lost."Rescuers" promised him to find her. However, when he finally meets her, he realized what they had done to her. She'd say 'Khol Do' for her salwar (bottom) on hearing any male voice, and she does that when her father speaks! The end of this story will leave you gasping for breath. But to a kid, who was going through sexual abuse, Manto made sense at 13 itself!

Try them

His stories will send a chill down your spine

Manto was tried for obscenity 6 times for his story 'Thanda Gosht', a story about a Sikh who loots a Muslim family and rapes their daughter only to realize he was raping a corpse all along! And in his other story, 'Toba Tek Singh', a Sikh (refusing to accept partition) stands on the border that divides India and Pakistan. As he falls in "no man's land", Manto subtly puts it, "There, behind barbed wire, was Hindustan. Here, behind the same kind of barbed wire, was Pakistan. In between, on that piece of ground that had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh." After 70 years of partition and several wars later, these lines still evoke a lot of emotions on both ends of 'sarhad'.

Yes, we do

Manto's tinge of madness and fearlessness is what we need

The 'madman' Manto was tried under Section 292 of the IPC for 'Kali Shalwar', 'Dhuan' and 'Bu'. Though he was acquitted, he was left feeling misunderstood and humiliated. In his world though, 'madmen' were the real people. That tinge of madness along with his fearlessness, his understanding of the human psyche, fight for free speech, his intolerance towards religious intolerance resonate deeply in his writings. Hence, they are relevant even now.

Why?

But do we even (India & Pakistan) deserve Manto?

I remember my first copy of Manto, which was in Urdu, fell in the hands of my grandmother. She read one story, slapped me tightly and said "ladkiyan aisi wahiyat kitabein nai padhti." It was my first encounter with anti-Manto crusade. There have been many since then. It now scares me to think what would happen if Manto were to return back in real life? He would've looked at both the countries in horror and wouldn't find much of a difference since he left. He might look for his Bombay, his city, his love, his inspiration and would have found Mumbai instead. It's good for him that he is dead!

Has he really?

But has Manto really died?

Is it possible that over 60 years after his death while we recite him and Faraz and Elia in the same breath, he is there smiling at us, haunting us through those blank stares, and mocking at our binary prism of thoughts, our fear of an unseen God, and the atrocities and hatred we carry in the name of that God? Or maybe he's just as restless as he was while living? Though yes, Manto continues to live with us through his 22 collections of short stories, 5 of radio plays, three essays, two personal sketches, one novel, and many film scripts (no, he was not just a writer of partition and prostitutes), and a film that releases tomorrow.